It was dark outside when the phone rang; a glance at the clock revealed the day was still in its infancy, which explained why the funeral director’s brain did not want to engage. Years of experience prevailed however, and he answered the call, finding on the other end of the line a hospice nurse requesting their services for a death that had occurred in a home. Two people were required to go in those circumstances, so he woke up the second employee on the list, then crawled out of bed, put on the suit he had carefully laid across the chair the previous evening, and made his way to the funeral home.

Arriving at the house they found the driveway filled to overflowing, even though the hour was early. Very early. The number of cars outside reflected the number of people gathered inside, and a brief conversation with the family indicated most everyone present was a relation of some sort, particularly her children who had been by her side almost constantly since hospice had said she probably wouldn’t be with them much longer. At least not physically.

Before bringing in the cot which would carry their mother’s body from her home of 40+ years to their facility, the director explained what would happen next, gave them paperwork that would help guide them through the coming days, and asked if they had any questions. It was then one of the daughters spoke up.

“I don’t know what you normally do when someone’s hands look as bad as hers do, but please don’t cover them up.”

It was an odd request, especially at that moment, so the director sought clarification. Don’t cover them up? As in don’t place something over them . . . or perhaps don’t try to hide the bruises and scars? He had already noticed them when first arriving but hadn’t really thought much about what would happen as she was prepared for her visitation and service.

“Don’t cover them . . .” she was struggling to explain her request . . . “Don’t put make-up on them or anything.”

The director made notes then asked the family to step out so they could move her from the bed to the cot . . . from the house to the car . . . from her home to the funeral home.

When the workday began, the embalmer reviewed the paperwork before starting the process of preparing her body. Then he started questioning the request regarding her hands. He wanted to be certain he understood, especially given their condition, but the funeral director who made the removal assured him that was what they said. It was what the family wanted so it was what they would do. Or, in this case, not do.

The family arrived for their private viewing and were escorted into the room by the same director who had spoken with them at her home just a few days before. The first thing they did was look at her hands . . . which brought about a sigh of relief. Only then did they begin explaining their request. Motioning to the bruises, they told him how she was always hitting her hands on something, whether it was the corner of the kitchen counter or a door frame or a wayward rock while pulling weeds in her flower beds. They showed him the scar on her left hand, the one where she managed to burn herself while canning beans from the garden she planted every year. In better times those hands had cradled grandchildren and great-grandchildren, despite the painful arthritis that had stiffened and gnarled her joints. Every mark meant something. Every mark helped tell the story of her life, of how she had cared for them with little to no regard for the sacrifices she was making. Only then did the director understand their request. They didn’t want to hide the love written upon her hands.

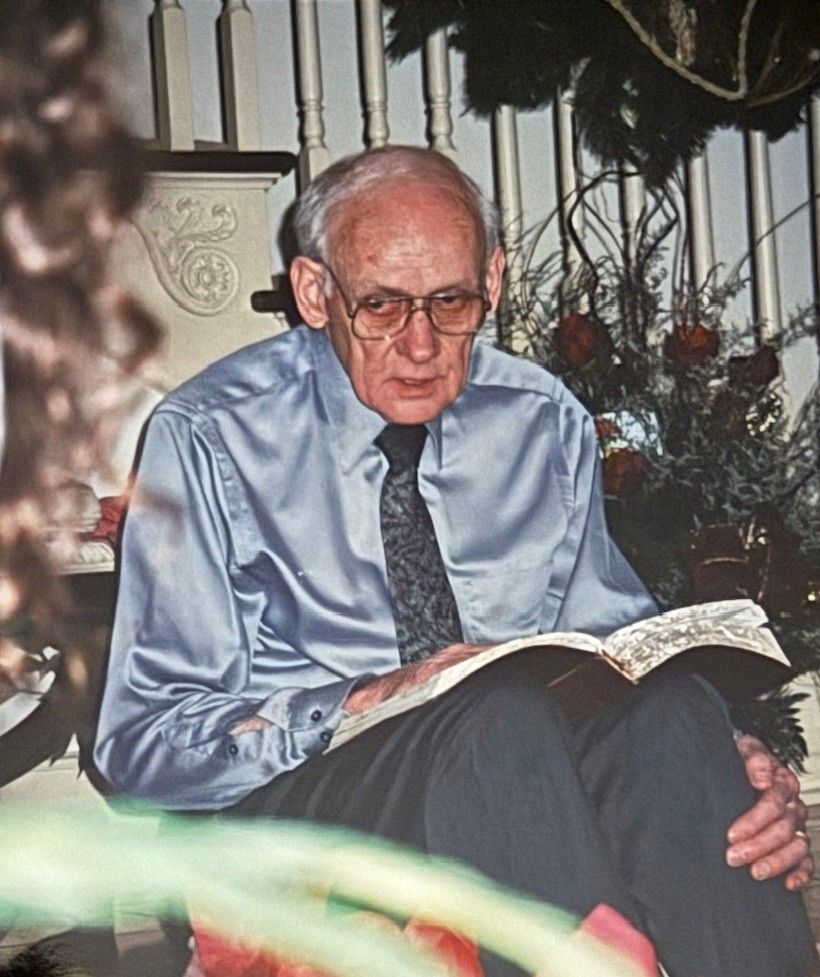

The aged things of this world are often the most meaningful because, in spite of everything, they have survived. They may be scarred and faded, battered and bruised, but they have weathered the tests of Time. And they still stand. Like the beautiful hands of their mother, these remind us of the things that matter the most. Whether it is an old house or an old monument, an old book or an old soul, they hold a beauty that is beyond compare—and a story all their own.

About the author: Lisa Shackelford Thomas is a fourth-generation member of a family that’s been in funeral service since 1926 and has worked with Shackelford Funeral Directors in Savannah, Tennessee for over 45 years. Any opinions expressed here are hers and hers alone and may or may not reflect the opinions of other Shackelford family members or staff.